……Old ‘peacebuilding’ schemes are obsolete in a country that is seeing new and ever-changing political and conflict dynamics.

The intense violence in this part of eastern DRC has been generally attributed to the Allied Democratic Forces, a Ugandan-origin rebel group that pledged allegiance to the Islamic State in 2019. As with previous massacres, none of the nearby military forces – including the Congolese army, invited Ugandan military or UN peacekeeping troops – intervened to stop the killing. This inaction reflects a broader politics of agony that has turned eastern DRC into a graveyard for thousands of civilians. At its roots is the failure of the mantra of good intentions professed by a divided and distracted “international community”. So, where did it all go wrong?

The M23 rebel leader in DRCongo, Brigadier-General Sultani Emmanuel Makenga.

The M23 rebel leader in DRCongo, Brigadier-General Sultani Emmanuel Makenga.

For the better part of the last three decades, the DRC has topped international counts of conflict-induced internal displacement – currently peaking at nearly 7 million, according to the International Organization for Migration. Meanwhile, human rights violations by both armed groups and government forces have cascaded. More often than not, concomitant cycles of violence and displacement have gone unnoticed.

It was only with the resurgence of the March 23 Movement (M23) nearly three years ago that the conflict attracted renewed international attention. While the ensuing fighting contributed to burgeoning displacement figures, the exclusive political and media framing focusing on M23 has ignored the proliferation of armed groups causing mayhem in the region. The government has used nationalist rhetoric to rally various militias to join the war effort against M23. This policy has empowered armed groups and produced an even more complicated security landscape. Meanwhile, international donors have continued to pump millions into conflict resolution, including an expensive, ageing UN peacekeeping mission, vast humanitarian funds and costly peacebuilding projects to stem “root causes.”

Thousands flee as fighting intensifies in eastern Congo.

Thousands flee as fighting intensifies in eastern Congo.

Largely missing, in what on paper looks like dedicated engagement, are an in-depth understanding of political realities, constructive strategy and innovative diplomacy at key levels of international decision-making.

Responses to the crisis in the DRC are often shaped by oversimplified interpretations of its root causes. Many pundits and influencers, including those on social media, recycle outdated colonial narratives that attribute the conflict to natural resource exploitation and ethnic hatred. Few commentators grasp the complex political nature of a crisis driven by multiple, interwoven factors.

Internally displaced people at Kanyaruchinya camp, Goma, Democratic Republic of the Congo. (Guylain Balume)

Internally displaced people at Kanyaruchinya camp, Goma, Democratic Republic of the Congo. (Guylain Balume)

Western donors, now commonly referred to as “international partners,” continue to apply one-size-fits-all, technocratic approaches to these political issues. While anticorruption rhetoric, regulation of “illicit” trade, and calls for social cohesion are prominent in polished strategy documents and press releases, actual efforts to address these challenges are often superficial or absent in practice.

International responses also remain largely inconsistent in the specific context of the current escalation. There is little pressure to discourage the Congolese army’s active collaboration with armed groups. Networks of grand corruption are rarely prosecuted and result in bizarre on-and-off sanctions sensitive to political shifts in the relations between DRC and key Western powers, such as the European Union or the United States. Responses to the military involvement of neighbouring countries are equally inconsistent. Western denouncement of Rwandan support for M23 does not stop the same governments from pushing for military aid to Rwanda in the context of the Mozambican crisis. Massive Burundian support to DRC received close to no international attention, even though it has further complicated the security landscape and led to a near proxy war situation between Burundi and Rwanda, heightening risks of further regional escalation.

People displaced by the M23 insurgency walk to makeshift shelters after receiving iftar food during the month of Ramadan at the Mugunga camp outside Goma, in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo.

People displaced by the M23 insurgency walk to makeshift shelters after receiving iftar food during the month of Ramadan at the Mugunga camp outside Goma, in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo.

This randomness and arbitrariness of a Western-leaning international community has not gone unnoticed by the Congolese people and their neighboring states.

As in similar ongoing conflicts, responses in the DRC showcase that classic international conflict resolution seems to have reached its limits and is losing much of its credibility – heralding the end of international peacebuilding and liberal interventionism in its current shape.

Contemporary conflict zones see new approaches and new actors scrambling for their place at the table. This is partly attributed to changing global power structures. Three decades of violence in eastern DRC have ticked all the boxes in the “bucket list” of Western intervention and state-building: the DRC had its first democratic elections in 2006; it underwent a peaceful political transition; the International Monetary Fund re-engaged with the country; and regional bodies are now taking over the peacekeeping baton.

Yet, amid wider geopolitical entanglements, non-Western forms of colonialism seek to replace the Western template, and private military companies also gaining ground.

M23 rebels withdraw from their positions in the town of Kibumba, Democratic Republic of Congo, Dec. 23, 2022 (AP photo by Moses Sawasawa).

M23 rebels withdraw from their positions in the town of Kibumba, Democratic Republic of Congo, Dec. 23, 2022 (AP photo by Moses Sawasawa).

The DRC and its rivals have turned to a range of new and not-so-new partners in business, defense and diplomacy. These partners are as ambiguous and interest driven as Western powers but without signposting human rights conditionalities and pro-democracy slogans.

Overall, the playing field of influence may not be as clear-cut as in Mali or the Central African Republic, where Russia, a new colonial actor, provoked a hard reset, kicking out France. The DRC presents a more intricate landscape. However, Western influence in the Great Lakes region is similarly fading, as new players exploit the long-standing paternalism of Western powers to establish their own footholds. In a restructured global power landscape, these actors are seizing opportunities through campaigns of disinformation and political polarization.

Democratic Republic of Congo’s President Felix Tshisekedi.

Democratic Republic of Congo’s President Felix Tshisekedi.

In this changing and increasingly fragmented international environment, the hypocrisy of old and new interveners is also somewhat mirrored by self-interested Congolese elites. These elites increasingly resort to outsourcing and sub-contracting national security to armed groups, private military companies and neighboring states. Such a hybrid context shows how security provision is no longer framed by international standards echoed by the UN that has not been able to achieve its global ambition. Leading to a fragmentation and privatization of security governance, in the case of the crisis in eastern DRC, these global and regional shifts will only add to the complex web of alliances and antagonisms that have already guided conflict drivers, interests and responses for decades.

These developments signal tectonic shifts, whether viewed through a geopolitical, realpolitik, or postcolonial lens. The humanitarian impact of this changing order is severe, compounding existing patterns of civilian suffering and displacement, while the obscured “fog of war” masks troubling trends in the global politics of security and insecurity.

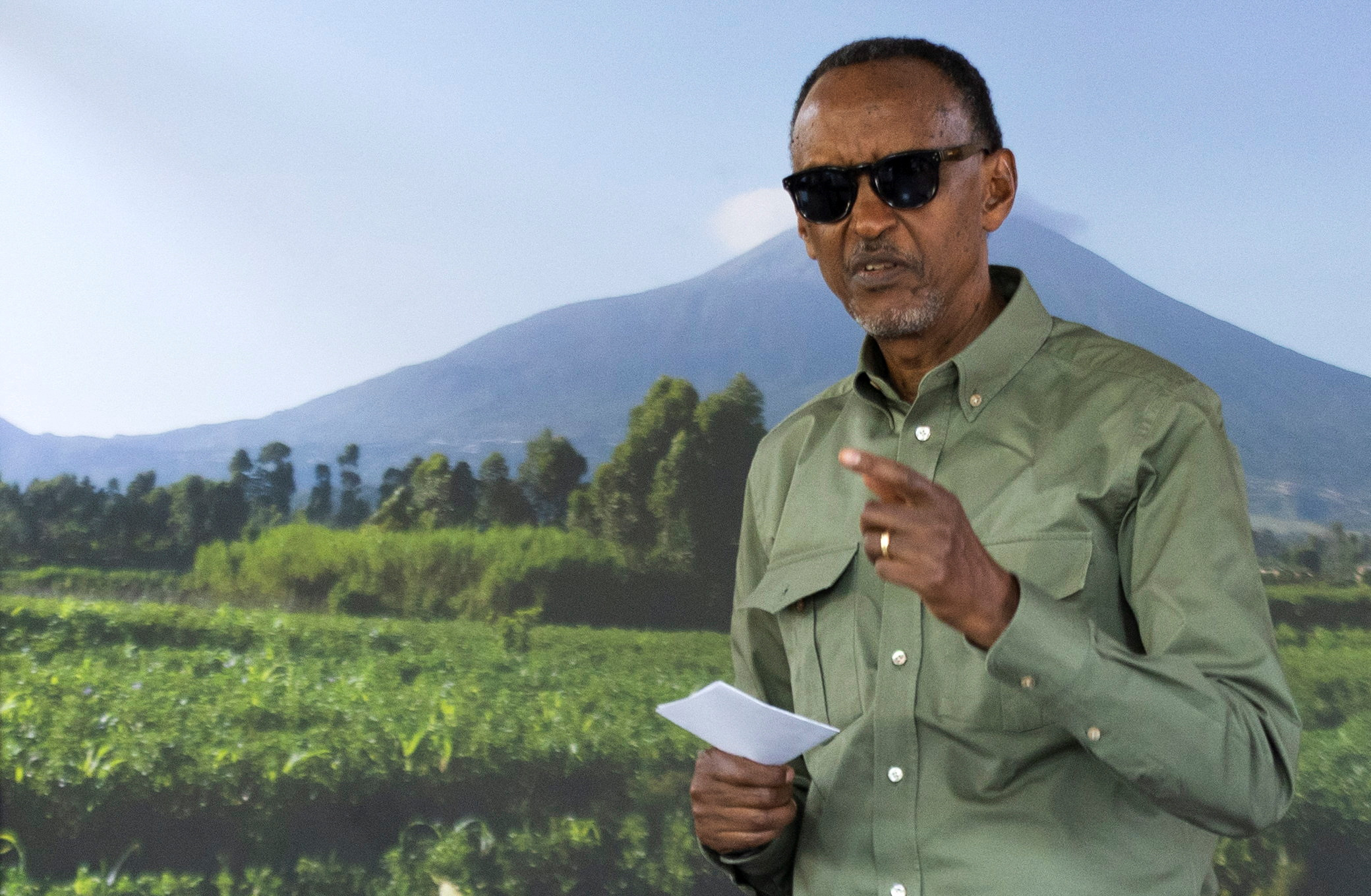

Rwandan President Paul Kagame, accused by DRC President Felix Tshisekedi and Western leaders of supporting M23 rebels and destabilizing the region.

Rwandan President Paul Kagame, accused by DRC President Felix Tshisekedi and Western leaders of supporting M23 rebels and destabilizing the region.

A clear-eyed and honest examination of these shifting dynamics is urgently needed, particularly for those representing the waning system of Western liberal interventionism and traditional conflict resolution.

(The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect AfrikTimes’ editorial stance.)

Koen Vlassenroot

Professor of Political Science at Ghent University

Koen Vlassenroot is a professor of political science at Ghent University, specializing in the study of civil war and armed mobilization.

Christoph Vogel

Senior Academic and Advisor

Dr. Christoph Vogel is a senior academic, advisor, and investigator with over 15 years of experience specializing in politics and conflict in the African Great Lakes region.